Drawing conclusions, to me, has always been something that we are expressly discouraged from doing in critical theory. The sectarian fuckery of what passes for a anti-capitalist movement in the United States is but one of many examples: consider the unending stream of “radical analysis” being churned out by counterculture celebrities eager to shed light on whatever new development is going to convince us to hate the government this week. What you never see in any of these essays is an actual conclusion, a finger pointed in an identifiable direction.

And god forbid you ever bring up an idea which actually has any implications to how we behave in the real world. The modern anarchist culture in particular has excelled in the last couple decades at policing itself to an extent in which anyone who dares to suggest some sort of quantifiable strategy to be utilized in the pursuit of a definite goal (aside from producing more theory, more analysis, and a more marketable image of anarchism uber alles) must be aggressively ignored.1

Although eventually I’d like to make “Drawing Conclusions” into a recurring theme on Song of the Cedars and go a little deeper into it, for now I just want to introduce the concept by focusing on a recent podcast which actually did not originate from the anti-capitalist milieu:

Image and text from Cracked.com

The Cracked Podcast itself is a new weekly series and at the time of this writing still has relatively few episodes, all of which can be easily accessed through the above links. Unlike most well-known podcasts, which tend to revolve around famous guest stars with plenty of experience in their given fields, Cracked’s has typically featured the site’s various staff members hanging out and spitting loose commentary on pop culture topics. All too often the results are a little sloppier than you’d like, but every once in a while you strike gold.

This episode features the usual host Jack O’Brien (Editor-in-Chief of Cracked.com) interviewing

Jason Pargin, Executive Editor of the same and a bestselling author under the pen name David Wong. Although neither of these dudes are well-recognized researchers of anything in particular, Pargin especially has carved out a place for himself on the Internet as an articulate man who has obviously taken some time to think about the things he’s trying to say.

“What American Can’t Admit About the ‘Millennial’ Generation” is really worth listening to in its own right, but for the purposes of this post I’d like to critique it a little bit from a communist perspective and try to fill in some of the gaps I felt like O’Brien and Pargin left in the discussion.

To quote Wikipedia, “Millennials… also known as Generation Y, are the demographic cohort following Generation X” and, “American sociologist Kathleen Shaputis labeled Millennials as the boomerang generation or Peter Pan generation, because of the members’ perceived tendency for delaying some rites of passage into adulthood for longer periods than most generations before them.”

Pargin and O’Brien begin the episode by introducing the Millennials we’re all blaming for high unemployment and presenting some statistics about the topic. They correctly correlate the current trend of anti-Millennial bias in the media with the similar manufactured panic we saw around Generation X back in the 1990’s. They point out that there are a lot of articles coming out about this newer generation that have a particular emphasis on their being lazy and entitled, often with an alarmist tone amounting to a fear for the future of civilization. Pargin’s first important point comes when he suggests that whenever you see a trend in the media towards sensationalizing or attacking something like the so-called Millennial generation, your reflex should be to ask why the dominant societal narrative is being geared towards making you hate that thing.

From there his analysis only gets more radical, though it can be said that he is simply following a logical train of thought. In Pargin’s own words, “…we’re kind of, I think, moving (in the first world at least) to a point where not everybody has to work in order to make society function, but we don’t know how to feel about that.”

The interview ultimately covers important territory regarding dominant narratives, consumerism, the military industrial complex and the fact that seemingly large numbers of young Americans would “rather be unemployed than work at jobs they hate”. Jack O’Brien asks what it means to arrive in a post-scarcity society when the justification behind the maintenance of that society had been based on the threat of starvation, which is a fairly radical line of inquiry. The fact that world hunger only exists because we throw away 50% of the food we produce is laid bare for examination, as is some of the reasoning behind the emerging concept of a guaranteed minimum income in some areas of public discourse.

The thrust of the arguments offered refer to the idea that since we’ve arrived at such a prolific system of production in the 21st Century, maybe not everybody actually has to work and furthermore maybe Millennials aren’t so crazy for not wanting to do menial service jobs. Possibly the most groundbreaking case made by Pargin is that the very concept of what a person brings of value to a society is changing. But if our notion of the value and purpose of a person’s life doesn’t depend on their functioning as a good consumer, then on what other basis can we direct human activity?

It is at this point that we first begin to see the more interesting implications of even having a discussion about the “Millennial crisis”. I almost fell out of my chair when I heard Jason Pargin ask rhetorically, “why did you build a road to last for like a hundred years if not so that the next generation wouldn’t have to do it?”.

In his classic The Conquest of Bread, Peter Kropotkin articulated an impassioned defense of communism by using a line of reasoning only a few degrees removed from Pargin’s comment about roads:

All the miners engaged in this mine contribute to the extraction of coal in proportion to their strength, their energy, their knowledge, their intelligence, and their skill. And we may say that all have the right to live, to satisfy their needs, and even their whims, when the necessaries of life have been secured for all. But how can we appraise their work?

And, moreover, Is the coal they have extracted their work? Is it not also the work of men who have built the railway leading to the mine and the roads that radiate from all its stations? Is it not also the work of those that have tilled and sown the fields, extracted iron, cut wood in the forests, built the machines that burn coal, and so on?

No distinction can be drawn between the work of each man. Measuring the work by its results leads us to absurdity; dividing and measuring them by hours spent on the work also leads us to absurdity. One thing remains: put the needs above the works, and first of all recognize the right to live, and later on, to the comforts of life, for all those who take their share in production. (Chapter XIII)

Kropotkin was explaining that the interconnected nature of civilization creates conditions where any new advance can be seen as having been dependent on the pre-existence of the society from which it sprung. This has practical implications in our modern world as newer generations increasingly come to recognize the sum total of humanity’s achievements in science, technology, and all the rest as social property, held in common as our global heritage.

And so we arrive at the rub: drawing conclusions. Implications. What, for a human being in the 21st Century looking at this issue of Millennials, is supposed to happen after we’ve discussed it to death?

For a listener armed with a Marxist analysis of the information being presented it is not only obvious but inevitable that certain conclusions must be drawn. And yet Pargin and O’Brien, despite possessing some pretty solid insights about the stage of history we’re living through, are forced to dance clumsily around the elephant in the room as they draw out the thread of their arguments only to finish by exasperatedly claiming that they have no idea what to make of it all. In a hesitatingly prescient exclamation towards the end of the interview Pargin admits that, “As a society we do a horrible job of connecting people with what they should be doing with their lives … The homeless are not homeless because we ran out of houses. There are more empty houses than there are homeless [people], but I’m not anywhere close to smart enough to know how you get those people in those houses without just destroying the entire system” (my emphasis).

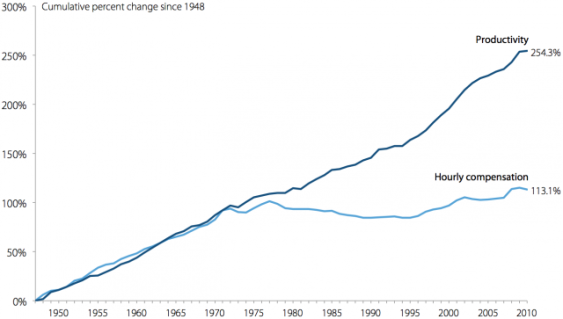

Note that productivity continued to rise even as unemployment shot up during the 2008 economic crisis.

Karl Marx understood that because the exploitation of labor is built into the structure of capitalism, increasing productivity does not translate into fewer hours worked or greater compensation but only fewer jobs, a leveling-off of profits, and a cyclical crisis of overproduction.

As with any dialogue which seeks to explore the fundamental questions before humanity, the radical content in this podcast is simmering right beneath the surface and at times may even be openly acknowledged (usually for the sake of dissuading us from thinking too hard about it). The irony of course is that even as the speakers tentatively explore an important contemporary topic and struggle to come to grips with it, the vocabulary and systematic analysis which would allow them to engage in a robust exploration of the concepts presented has already existed for over a century.

The unique utility, the beauty, of Marxism is that it gives us tools with which to engage with the dominant social trends of an era and suss out a little bit of what’s happening in the greater context of human history. In short, it allows us to draw some conclusions.

In this case, according to Pargin, we are seeing the rise of a mass youth consciousness which turns away from the conditioned belief that wage slavery is the only valid use of one’s life. From there, according to me, it does not take much to realize that to many Millennials, the world political and economic system is so inherently corrupt and exploitative that there really isn’t much of an argument to be made for participating in its daily recreation.

Much as Marx was predicting over 150 years ago, the breakneck development of the capitalist system, the division of labor and the ubiquity of automation has reduced the amount of work truly necessary for the maintenance of society to levels previously only speculated on in science fiction. However, because capitalism is driven by mechanical imperatives toward profit and cannot accommodate this changing set of conditions, the sum of human economic activity becomes so grossly wasteful and inefficient that even with the vast sophistication of our current system we are unable to provide even a basic standard of living for the inhabitants of our planet.

Thus the argument for a new method of organizing human society, for socialism, gains increasing credibility based simply on the material conditions at work in the daily lives of millions of people. This sea change in mass consciousness is only at an embryonic stage, but already there are some indications, the Cracked Podcast being one of them, that American and certainly global awareness of these issues is reaching a tipping point. The task for communists, as ever, is to try and ensure that someone out there is brave enough to draw conclusions.

Footnotes:

1. It’s entirely tangential to the topic of this post, but I would argue that the failure of North American anarchism can best be understood through this lens.

Appendix A: Other interesting Cracked Podcasts featuring Jason Pargin:

- Why America Loves to Freak Out About Made Up Crime Waves

- Why Every Movie Plot Follows Weirdly Specific Rules

- The BS Underdog Story Americans Believe Over and Over Again

- Why People Born After 1995 Can’t Understand the Book ‘1984’

Appendix B: While looking up that Kropotkin quote I was pointed to a similar passage from Alexander Berkman’s later What is Communist Anarchism?, another notable contribution to the communist literature of the period. I’m going to quote it here even though it’s a bit lengthy, because it’s fucking awesome:

“You said that Anarchy will secure economic equality,” remarks your friend. “Does that mean equal pay for all?”

It does. Or, what amounts to the same, equal participation in the public welfare. Because, as we already know, labor is social. No man can create anything all by himself, by his own efforts. Now, then, if labor is social, it stands to reason that the results of it, the wealth produced, must also be social, belong to the collectivity. No person can therefore justly lay claim to the exclusive ownership of the social wealth. It is to be enjoyed by all alike.

“But why not give each according to the value of his work?” you ask.

Because there is no way by which value can be measured. That is the difference between value and price. Value is what a thing is worth, while price is what it can be sold or bought for in the market. What a thing is worth no one really can tell. Political economists generally claim that the value of a commodity is the amount of labor required to produce it, of “socially necessary labor,” as Marx says. But evidently it is not a just standard of measurement. Suppose the carpenter worked three hours to make a kitchen chair, while the surgeon took only half an hour to perform an operation that saved your life. If the amount of labor used determines value, then the chair is worth more than your life. Obvious nonsense, of course. Even if you should count in the years of study and practice the surgeon needed to make him capable of performing the operation, how are you going to decide what “an hour of operating” is worth? The carpenter and mason also had to be trained before they could do their work properly, but you don’t figure in those years of apprenticeship when you contract for some work with them. Besides, there is also to be considered the particular ability and aptitude that every worker, writer, artist or physician must exercise in his labors. That is a purely individual, personal factor. How are you going to estimate its value?

That is why value cannot be determined. The same thing may be worth a lot to one person while it is worth nothing or very little to another. It may be worth much or little even to the same person, at different times. A diamond, a painting, or a book may be worth a great deal to one man and very little to another. A loaf of bread will be worth a great deal to you when you are hungry, and much less when you are not. Therefore the real value of a thing cannot be ascertained; it is an unknown quantity.

But the price is easily found out. If there are five loaves of bread to be had and ten persons want to get a loaf each, the price of bread will rise. If there are ten loaves and only five buyers, then it will fall. Price depends on supply and demand.

The exchange of commodities by means of prices leads to profit making, to taking advantage and exploitation; in short, to some form of capitalism. If you do away with profits, you cannot have any price system, nor any system of wages or payment. That means that exchange must be according to value. But as value is uncertain or not ascertainable, exchange must consequently be free, without “equal” value, since such does not exist. In other words, labor and its products must be exchanged without price, without profit, freely, according to necessity. This logically leads to ownership in common and to joint use. Which is a sensible, just, and equitable system, and is known as Communism.